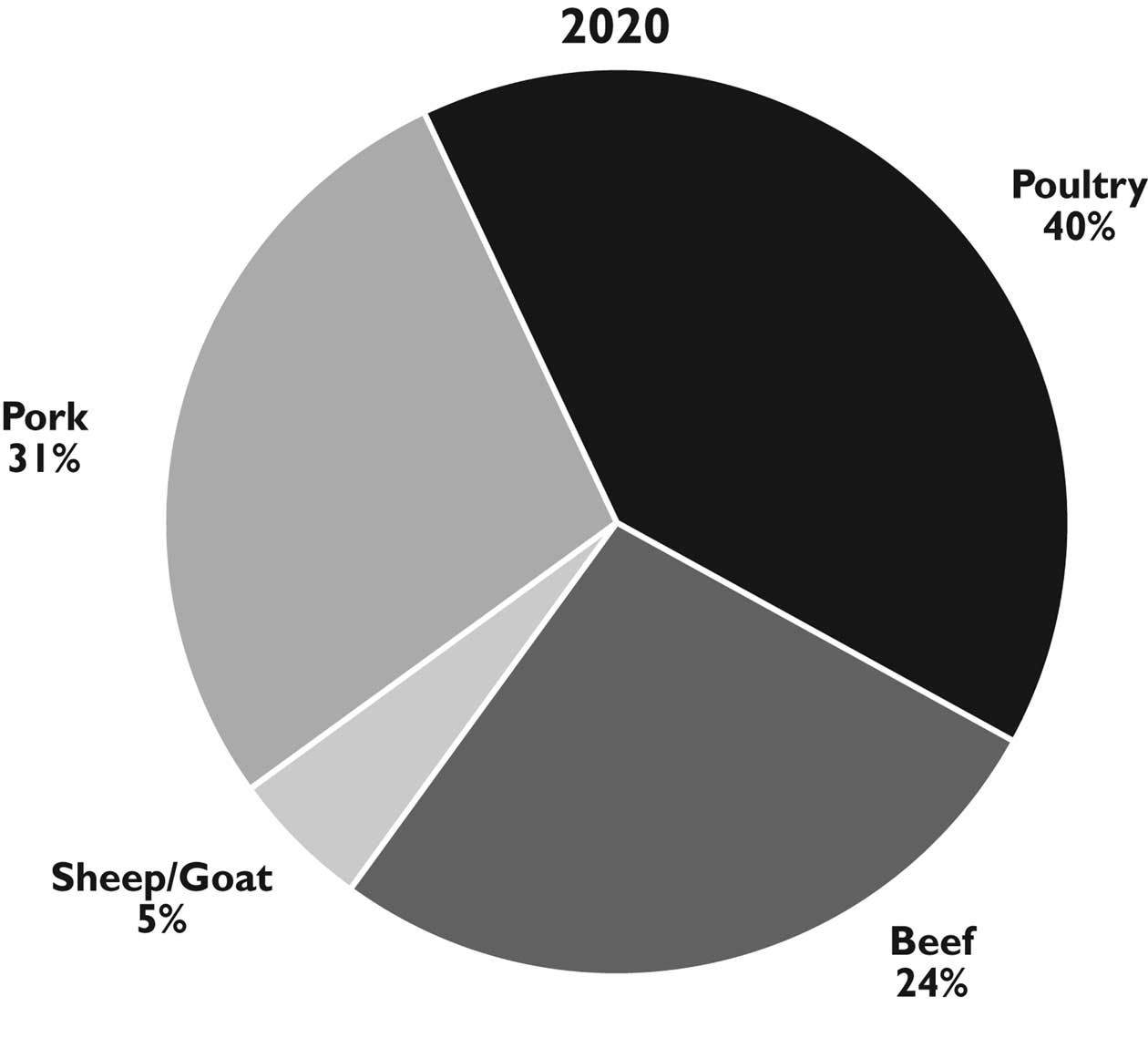

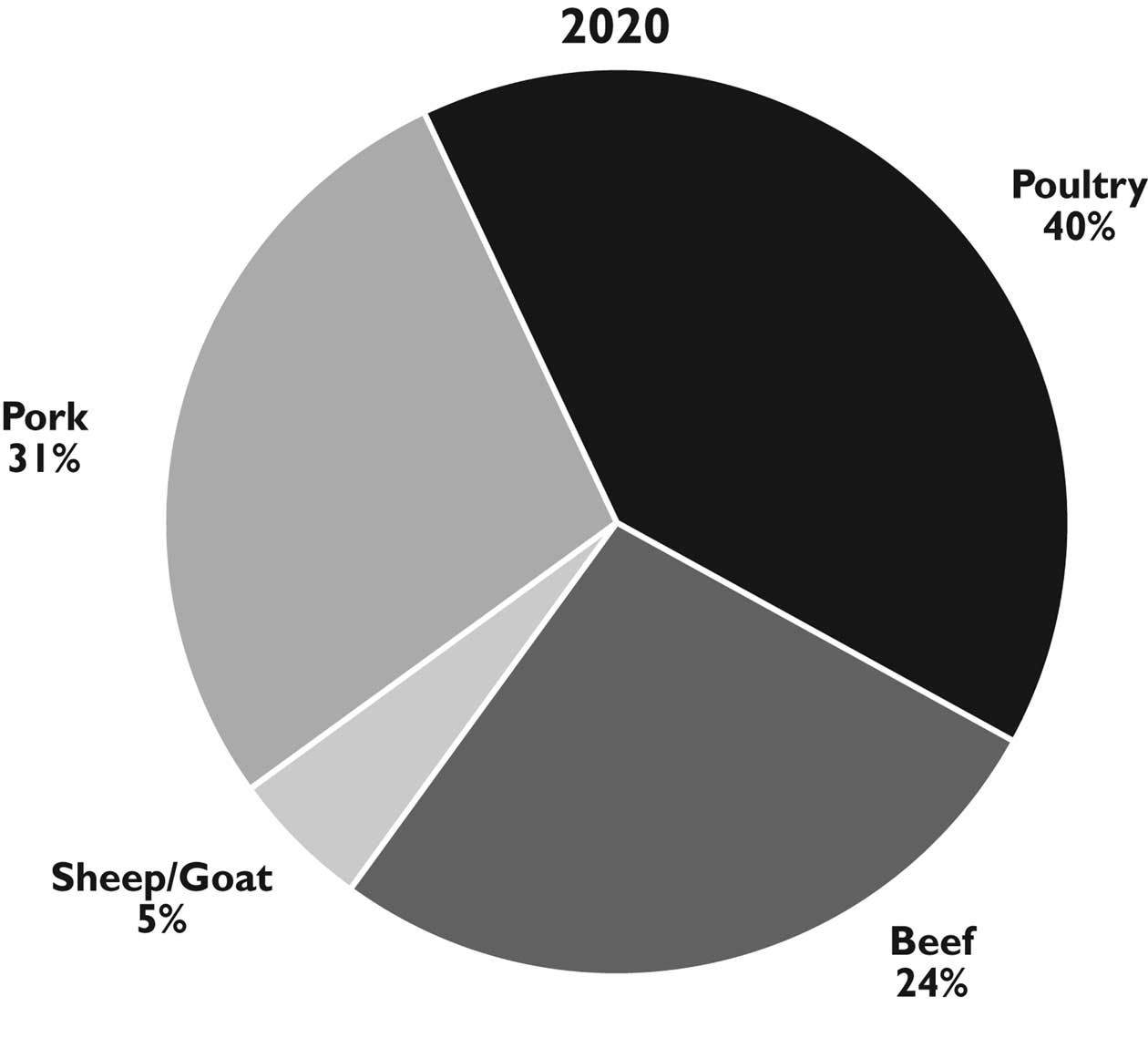

Figure 4-8. Increase in demand for meat. Increase in demand for meat 1997-2020.

Source: Rosegrant et al., 2001 based on IFPRI IMPACT projections.

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

Food Systems and Agricultural Products and Services towards 2050 | 93

Figure 4-8. Increase in demand for meat. Increase in demand for meat 1997-2020.

Source: Rosegrant et al., 2001 based on IFPRI IMPACT projections.

environment for the private sector through policies involving taxation and marketing. Mill usage in SSA is projected to create additional jobs and generate income for more people. Floriculture and horticulture. SSA competitiveness in the floriculture sector will depend on successful marketing and use of ICT, including date information on markets and their sizes, product demand, education and extension on production, processing, and handling. This sector will be increasingly competitive (Table 4-5) (Kane et al., 2004; Minot and Ngigi, 2004; CIAT, 2006). The trade in fresh fruits and vegetables with Europe will depend on the level of consumption and population growth (Table 4-6). Exporters from SSA will also have to meet the changing standards and certification requirements, including in the organic market (Collinson, 2001; NRI, 2002; Smelt and Jager 2002; Jaffee, 2003; Hallam et al., 2004). As eating patterns in the developed world become healthier, (e.g., increased fruit and vegetable consumption), there will continue to be demand for fresh horticultural products year round. A stable economic and political climate will be needed for investor confidence. Infrastructure such as roads, airport facilities, information and communication systems, reliable power and water supply, control, testing and certification services will be required to ensure competitiveness. Agroecosystem tourism. Tourism and agroecotourism in particular in SSA will remain viable towards 2050. Tourist arrivals are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 7% per year until 2020 (WTO, 2005). Though agro- |

ecotourism is believed to propel economic development, its social acceptance in SSA will continue to depend on opportunities presented to local communities. The recognition of agroecotourism’s growth potential will have a positive impact on investments in many SSA countries and is poised to contribute to key sustainability and development goals (Giuliani, 2005). Carbon sequestration and trade. The Kyoto Protocol’s

Clean Development Mechanism will enable industrialized

countries to set up carbon offset projects in SSA. Carbon

investments are projected to reduce poverty and protect vulnerable

ecosystems. The present carbon trade project in SSA

constitutes less than 10% of the international carbon trading.

The situation is set to change with the entry of Kyoto

compliant projects and numerous voluntary emissions with

incentives from the World Bank’s BioCarbon Fund (World

Bank, 2006). payment for ecosystems services. To appreciate the longterm

value of environmental services from agroecosystems,

new institutional mechanisms will be needed to develop

effective markets for ecosystems goods and services. This

includes mechanisms for the operationalization of the costs

of environmental

damage and the benefits of environmental

protection into agricultural production and marketing decisions

and policy. Such efforts are likely to be most successful

in countries where there is a clear, politically expressed perception

of environmental scarcity or threat. This will likely

happen in areas of population or production

pressures, rural |

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||