| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

Options for Action | 245

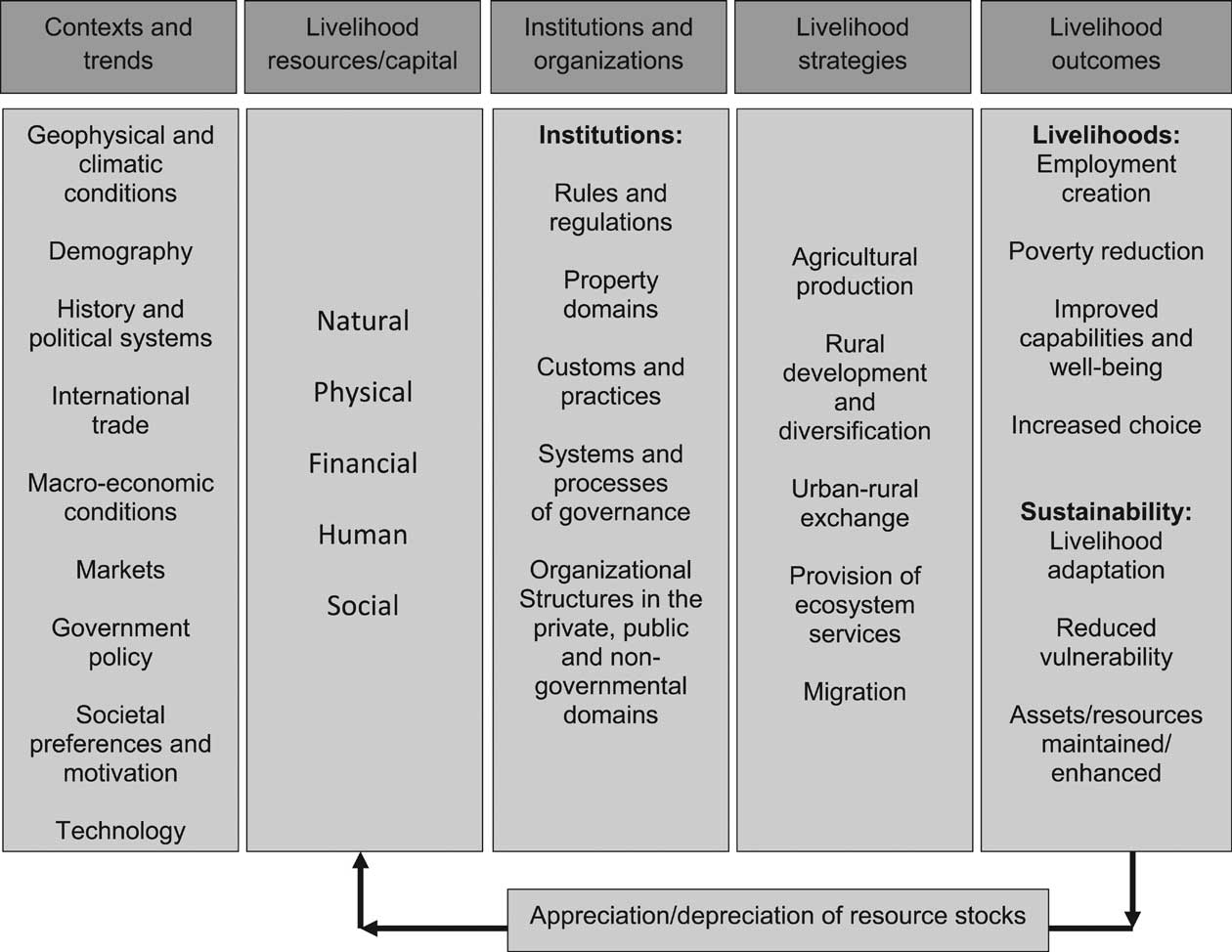

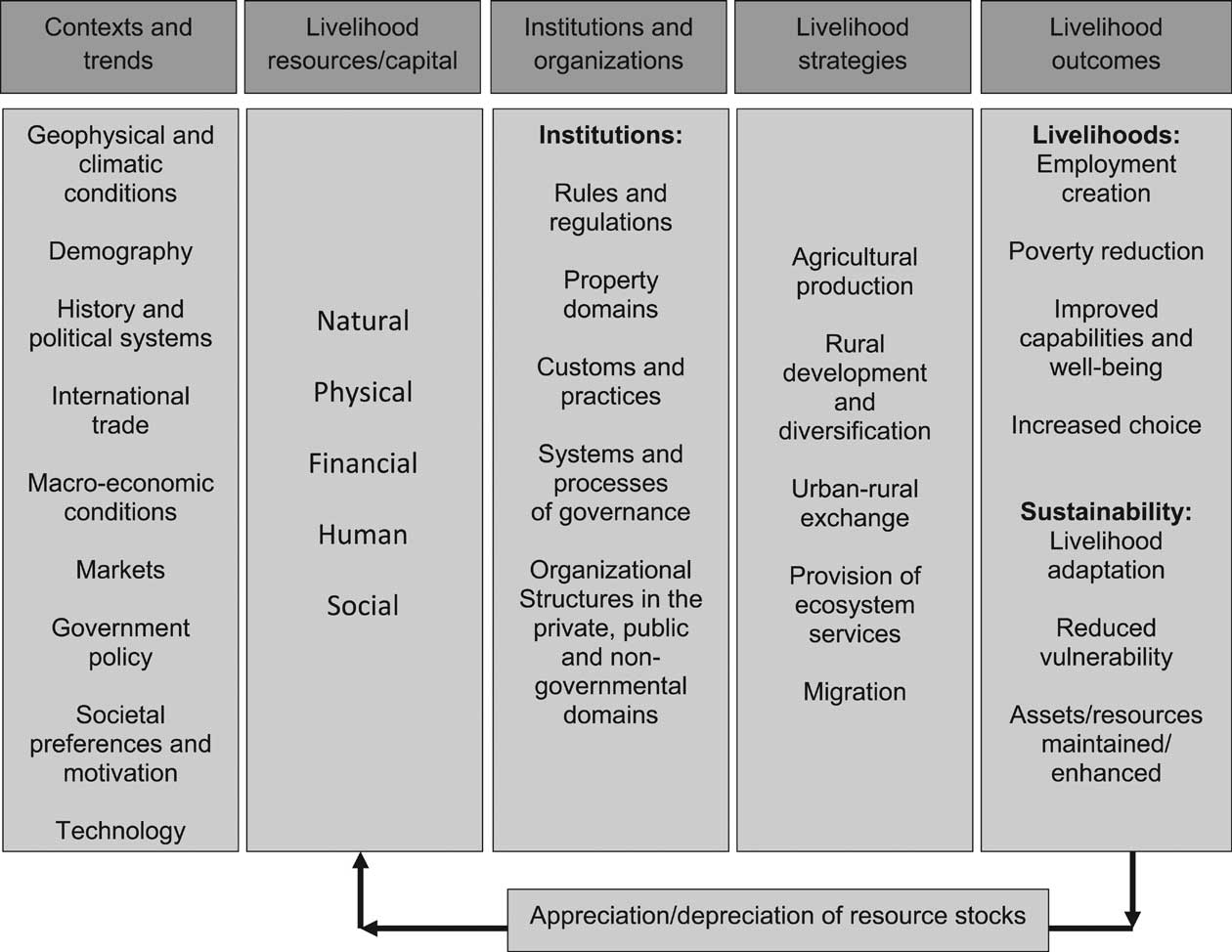

Figure 6-1. Framework for the analysis of sustainability. Source: Adapted from Scoones, 1998, DFID, 1999.

tems and management practices, as well as the social and economic outcomes for farming families and communities. 6.2.10.4 Understanding farmer attitudes and behavior |

|

ties (Ryan and Goss, 1943; Rogers, 2003). Prior conditions, such as policy drivers or perceived needs, shape the disposition of potential adopters towards a new product or practice. This process is influenced by characteristics of decision makers (such as personal and contextual social, economic and cultural factors) and characteristics of innovations (such as relative advantage, compatibility with values and preferences, simplicity and ability to trial and observe benefits). These models also confirm the importance of communication channels, agents of change and contextual and cultural factors, including the relative balance of individual and collective decision making. These models have however been criticized as too rigid, seeing adoption as an externally driven, linear process. Alternative models emphasize different elements of the decision process, namely systems models, information models, models of reasoned action and learning and knowledge transfer models (Garforth and Usher, 1997; Beedell and Rehman, 1999; Morris et al., 2000; Phillipson and Liddon, 2007). |

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||