| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

224 | IAASTD Global Report

|

"disconnects" between agriculture and the sectors dealing with (1) food processing, (2) fibre processing, (3) environmental services, and (4) trade and marketing and which therefore limit the linkages of agriculture with other drivers of development and sustainability. The challenge for the future is for agriculture to increasingly develop partnerships and institutional reforms to overcome these "disconnects". To achieve this it will be necessary for future agriculturalists to be better trained in "systems thinking" and entrepreneurship across ecological, business and socioeconomic disciplines. Ninth, AKST has suffered from poor linkages among its key stakeholders and actors. For example: (1) public agricultural research is usually organizationally and philosophically isolated from forestry/fisheries/environment research; (2) agricultural stakeholders (and KST stakeholders in general) are not effectively involved in policy processes for improved health, social welfare and national development, such as Poverty Reduction Strategies; (3) poor people do not have power to influence the development of prevailing AKST or to access and use new AKST; (4) weak education programs limit AKST generation and uptake (especially for women, other disadvantaged groups in society and formal and informal organizations for poor/small farmers) and their systems of innovation are not well connected to formal AKST; (5) agricultural research increasingly involves the private sector, but the focus of such research is seldom on the needs of the poor or in public goods, (6) public research institutions have few links to powerful planning/finance authorities, and (7) research, extension and development organizations have been dominated by professionals lacking the skills base to adequately support the integration of agricultural, social and environmental activities that ensure |

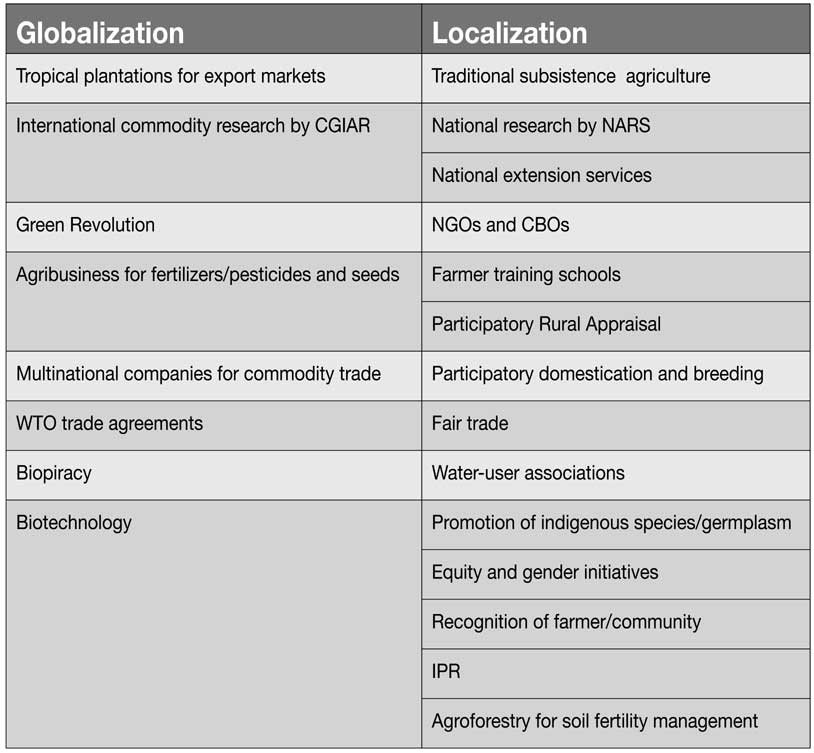

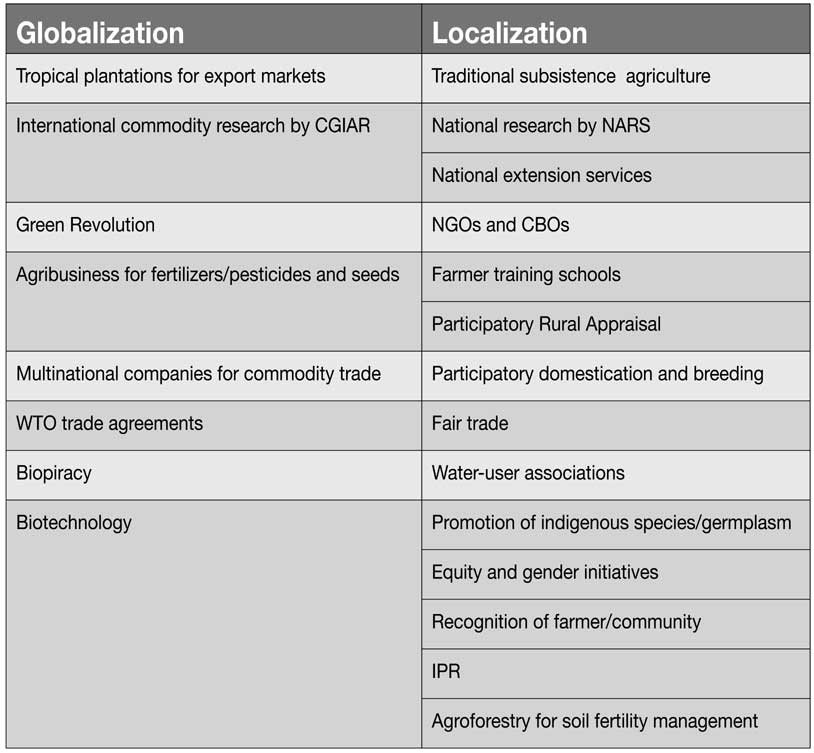

the multifunctionality of agriculture, especially at the local level. The main challenge facing AKST is to recognize all the livelihood assets (human, financial, social, cultural, physical, natural, informational) available to a household and/ or community that are crucial to the multifunctionality of agriculture, and to build systems and capabilities to adopt an appropriately integrated approach, bringing this to very large numbers of less educated people-and thus overcoming this and other "disconnects" mentioned earlier. Finally, since the mid-20th Century, there have been two relatively independent pathways to agricultural development- the "Globalization" pathway and the "Localization" pathway. The "Globalization" pathway has dominated agricultural research and development, as well as international trade, at the expense of the Localization; the grassroots pathway relevant to local communities (Table 3.5). As with any form of globalization, those who are better connected (developed countries and richer farmers) tend to benefit most. The challenge now is to redress the balance between Globalization and Localization, so that both pathways can jointly play their optimal role. This concept, described as Third-Generation Agriculture (Buckwell and Armstrong-Brown, 2004), combines the technological efficiency of second-generation agriculture with the lower environmental impacts of first-generation agriculture. This will involve scaling up the more durable and sustainable aspects of the community-oriented "grassroots" pathway on the one hand and thereby to facilitate local initiatives through an appropriate global framework on the other hand. In this way, AKST may help to forge and develop Localization models in parallel with Globalization. This approach should increase benefit flows to poor countries, and to marginalized people everywhere. This scaling up of all the many small |

|

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||